Around Halloween, an image we see with more frequency in the U.S. are of people with intricately, colorful painted skulls on their face and vibrant costumes. It is related to a Mexican tradition, a celebration called Dia de los Muertos, “The Day of the Dead”. Each year the images grow in popularity and this year we noticed an explosion of artistic exhibits related to this mixture of spooky and colorful display. Given the great response to our Instagram post, I wanted to write this blog post to share the history in more detail. In addition I have shared several exquisite designs to showcase the beautiful artistry it has elevated to today.

Dia de los Muertos is not a Mexican version of Halloween, although it is celebrated on November 1 and 2. Originally celebrated in August it was changed to coincide with the Western Christian triduum of All Saints Eve (Oct 31), All Saints Day (Nov 1) and All Souls Day (Nov 2) and the fall maize harvest. The modern day version of Day of the Dead dates back hundreds of years to an Aztec festival practiced by indigenous people of central and south Mexico and fused with European Christianity. However the act of celebrating the dead goes back 2500 to 3000 years ago during pre-Columbian era. It was not until the 21st century when northern Mexico adopted the tradition and the president of Mexico then declared it a national holiday.

While the theme is death, the Day of the Dead is an event unfolding over two days in an explosion of color and life-affirming joy. Friends and family prepare and awaken the dead spirits in celebration of their life. What a wonderful way to remember and honor our beloved deceased rather than a somber reunion.

DAY ONE, THE PREPARATIONS

Designer Jessica Renendiz created this headpiece for Dia de los Muertos using baked bread and butterflies as symbolic adornments

In the first day, ofrendas or altars are prepared. It is the centerpiece not for worshipping but for welcoming the spirits. Hence it is covered with family photos, candles-one for each dead person, marigold flowers and food. Pan de muerto (baked bread) is made. The idea is to prepare the favorite foods and drinks of the deceased. Pan de muerto is a type of sweet roll shaped like a bun with sugar atop. Since many towns did not have funeral homes, the idea was that friends and neighbors would assume the task of making the preparations and bringing the food, especially the bread, to the homes of the relatives of the deceased for the wake. This was a show of support. The same supporters would also conduct other chores such as laundry, cleaning the home and digging the burial site. This practice continued until the 1970s when funeral homes took over the process of the wake, the vigil, the burial and feeding the visitors.

Hasta en el Velorio, Las Penas con Pan son Menos

Even during a wake, less are the sorrow and pain when sharing bread

In the images above and below, Mexican designer Jessica Resendiz cleverly incorporates pan de muerto into a headpiece. Jessica shares she was celebrating her grandmother who passed away last year. She also added a butterfly after she encountered many of them since her grandmother’s passing. Deeply moved by the symbolism, she felt it was necessary to add it to her design and garb. The skill and talent is incredible. Clearly this is highly artistic and one of our favorites.

Jessica Renendiz remembers and celebrates her deceased grandmother with this elaborate artistic headpiece and garb

In Mexico today where this celebration is practiced for generations, the designs and costumes will not be as elaborate. These are small towns and families with limited resources but nonetheless they practice with the utmost devotion, energy and creativity.

“Catrinas” pose in Mérida, Mexico for Dia de los Muertos

Cleaning the Cemetery & Decorating Graves

Another part of the preparation, a Dia de los Muertos tradition is to clean up the cemetery by removing weeds, clearing it of any rubbish and beautifying tombstones.

Adult graves are marked with yellow marigolds while a child’s grave is beautified with white orchids.

Cleaning the cemetery and decorating tombstones in preparation for Dia de los Muertos

DAY TWO, November 2, THE CELEBRATION

So the big celebration of parades, music, dance, and eating culminates on the second day, November 2. Bringing and consuming the favorite foods and beverages of the deceased is part of the celebration while recounting special or humorous moments. It’s about community and celebration.

Calaveras de Azucar (Sugar Skulls)

The most common symbol of the Day of the Dead is the calaveras (skulls) and calacas (skeletons). It is common to decorate them in bright colors and either eat them or leave them for the deceased in ofrendas (small personal altars) or grave sites. This sugar art tradition was brought by 17th century Italian missionaries.

Hence the image we see now in the commercialization of this tradition is variations of this colorful clipart seen below.

A colorful skull – a common symbol for Dia de los Muertos

Historians agree, it was not until 50 years ago that sweet candies were purchased or used to celebrate Halloween or All Soul’s Day.

Drinks

Include pulque, a sweet fermented beverage made from the agave sap; atole, a thin warm porridge made from corn flour with unrefined can sugar, cinnamon, and vanilla added; and hot chocolate.

Costumes

This is an extremely social holiday that spills into streets and public squares. Dressing up in fancy suits or dresses, artfully painted skulls on faces mimicking Catrina is all part of the fun. Today costumes are becoming more intricate in design as we have seen in these images.

Papel Picado

Artisans stack colored tissue paper in dozens of layers, then perforate the layers with hammer and chisel. The paper is then draped around altars and the art represents the wind and the fragility of life.

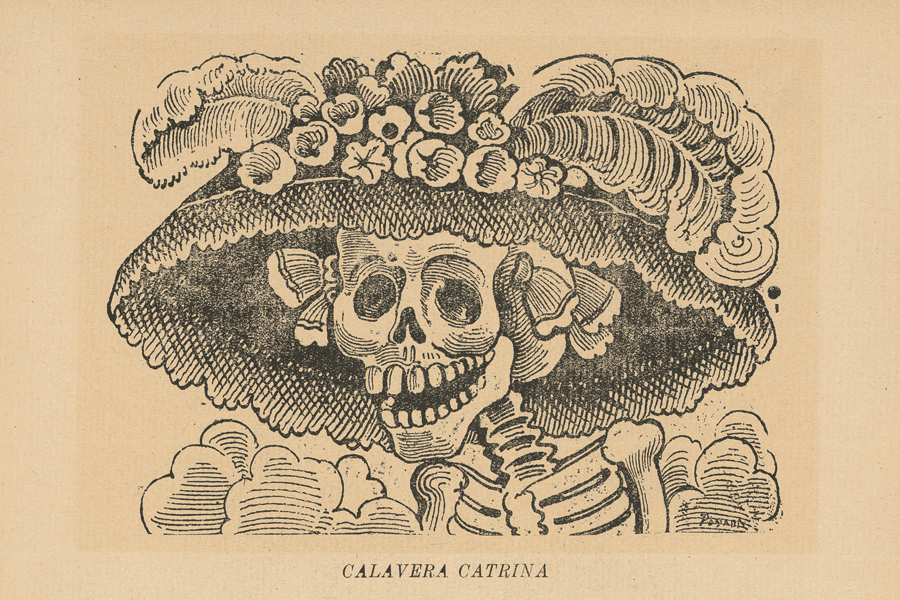

Calavera Catrina

In the early 20th century Mexican political cartoonist Jose Guadalupe Posada etched a figure of death dressed in fancy French garb intending it as a social commentary on Mexican society’s emulation of European sophistication. “Todos somos calaveras”, “we are all skeletons”. Underneath our manmade trappings, we are all the same. Posada named his stylized skeleton dressed in a large feminine bourgeois hat, “Catrina” slang for the “the rich”.

Originally designed by Jose Guadalupe Posada

In 1947 Mexican artist Diego Rivera added color to Catrina, thus awakening her spirit. Today the Calavera Catrina, or elegant skull, is the Day the Dead’s most ubiquitous symbol.

Colorized by Mexican artist Diego Rivera

Francisco Parraguirre is one of our favorite Catrina visual artists. Living in Bakersfield, CA, he has gained recognition and an impressive Instagram @catrinadivinaofficial following for his work. Below is Francisco as Calavera Catrina.

Visual artist Francisco Parraguirre dressed as Calavera Catrina

UNESCO Recognizes the Cultural Holiday

Thanks to UNESCO, the term “cultural heritage” is not limited to monuments and collections of objects. It also includes living expressions of culture–traditions passed down from generation to generation. In 2008 UNESCO recognized the importance of Dia de los Muertos as a holiday. Today Mexicans from all religious and ethnic backgrounds celebrate Dia de los Muertos, but at its core, the holiday is a reaffirmation of indigenous life.

Francisco Parraguirre from @catrinadivinaofficial on Instagram

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed writing this post for various reasons. First it allowed me to present the Mexican culture which is not a dominate one in Miami as it is in Texas, Arizona or California. A lovely change of pace from our tours which focus mostly on the Cuban culture. Second, I loved scrolling through pages of images. At one point I prepared margaritas and toasted corn to continue watching and enjoying the show. A single photo with the magnificent details tell a story–about the artist, or the deceased, or the living relative. This was better than going to the movies. A modern day fusion of e-galleries and movie storytelling all in one sitting. I hope you enjoyed reading this post and perhaps learned something new.

To view more fantastic artistry and photography, visit our Instagram page.

Mexican Population in Miami

While Miami is home to all Hispanic groups, the Mexican and Mexican American population accounts for the smallest group, only 60,000 in Miami Dade County, or 2.14% of the total population. While Hispanics accounts for 70% of the total county population, Mexicans account for 3.061% of Hispanics in Miami Dade according to a 2020 Census forecast.

Written by Christine Michaels, founder of Little Havana Tours, Miami, FL